Historical Fire Regimes

Role of Fire In Missouri

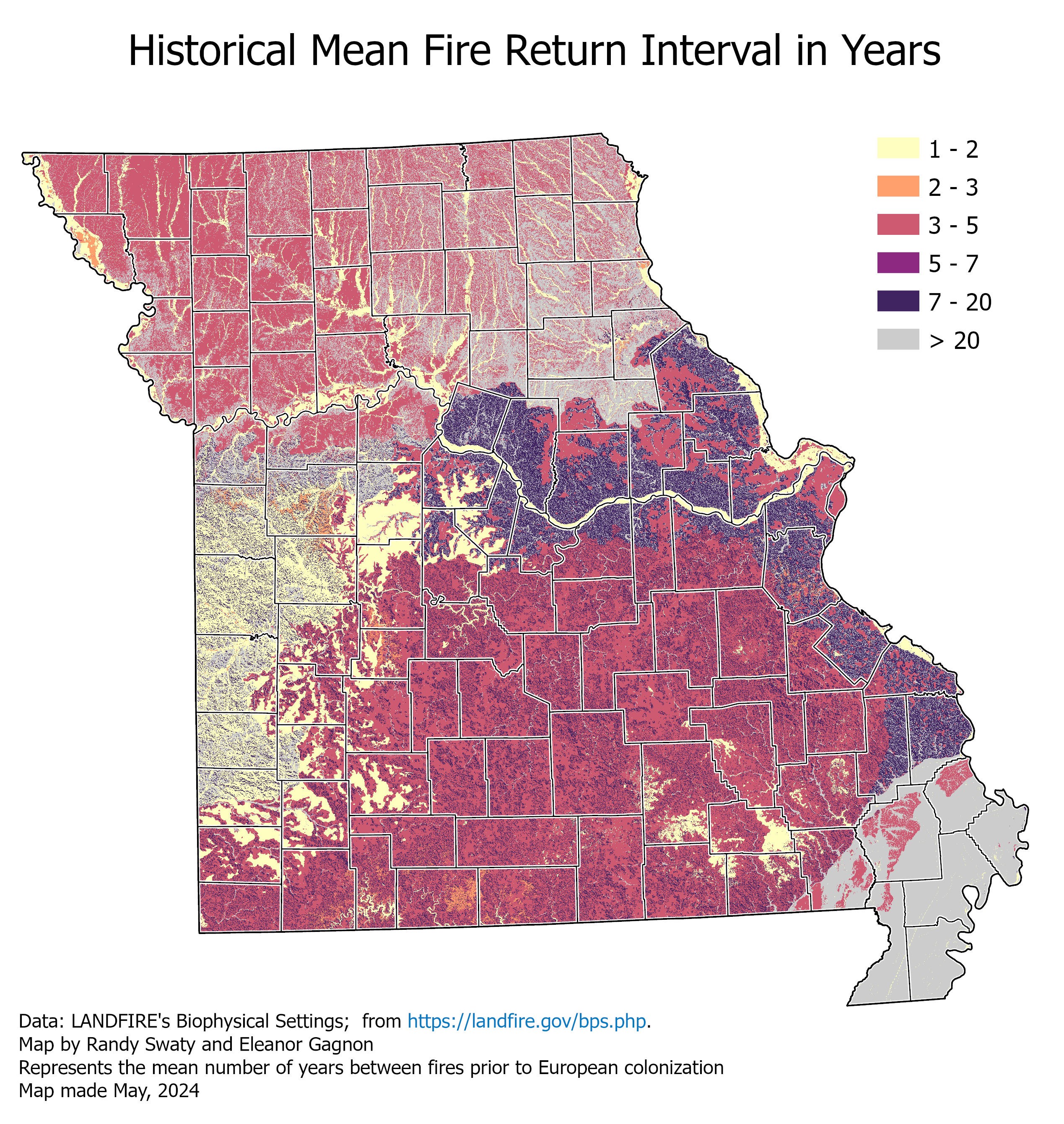

Historically, most of Missouri has had fire regularly moving across its landscape– much of it seeing multiple fires within a 10 year period as seen in the map to the right created with LANDFIRE’s Biophysical Settings data (See About page.). While this is not a prescription for what should happen today, the past provides important context and acts as a guide for assessing our current needs.

Recent research has found that until 100 years ago fire was used extensively as a landscape management tool, shaping much of Missouri’s natural environments (Vaughn, 2024). Prior to European settlement, Native Americans transformed the ecosystems around them to suit their survival needs using wide-scale burning, agriculture, hunting, and more. In fact, according to the Missouri Comprehensive Conservation Strategy report;

“it is estimated that humans have utilized fire for more that 70 different purposes such as to clear the landscape to plant crops, as a weapon against enemies, as a hunting tool, and as a tool to improve grazing for big game.” (Missouri CCS, 2022, p. 144)

Beyond the benefit to Missouri’s human population, the wide-scale use of fire provided many benefits for Missouri’s flora and fauna. It improved wildlife habitats and hunting conditions, as well produced a region of varied and abundant prairie, glade, savanna, woodland and forest communities.

Historic Burn Patterns

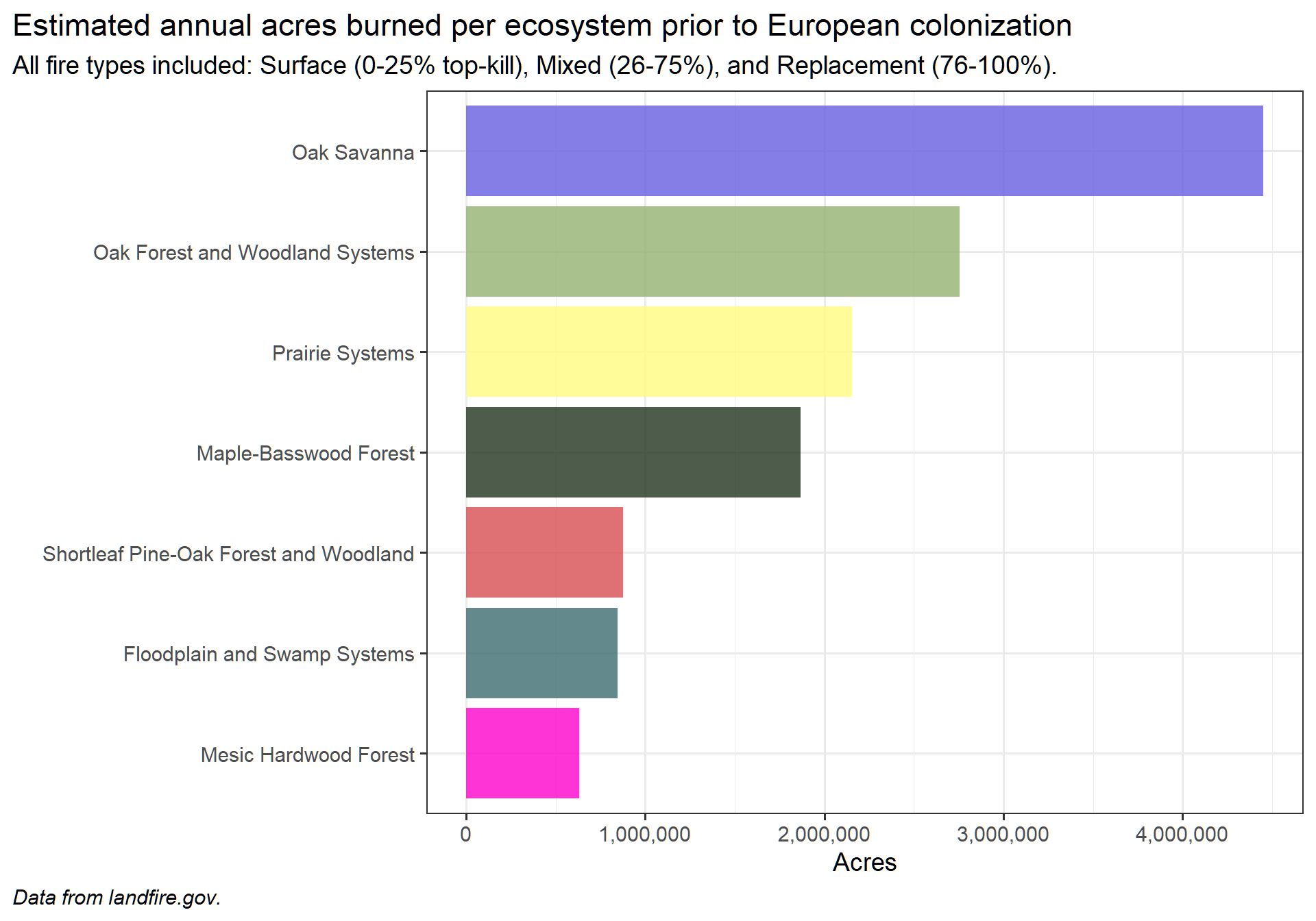

In the past, every ecosystem would have had its own Mean Fire Return Interval (MFRI), and extent. The chart below shows just how much variety in historical annual acres burned there was depending on ecosystem type as well as how extensively fire would affect them per year. Today, only an estimated 125,000-150,000 acres total are burned per year. In comparison, over 2 million acres of prairie systems alone would have burned prior to European settlement.

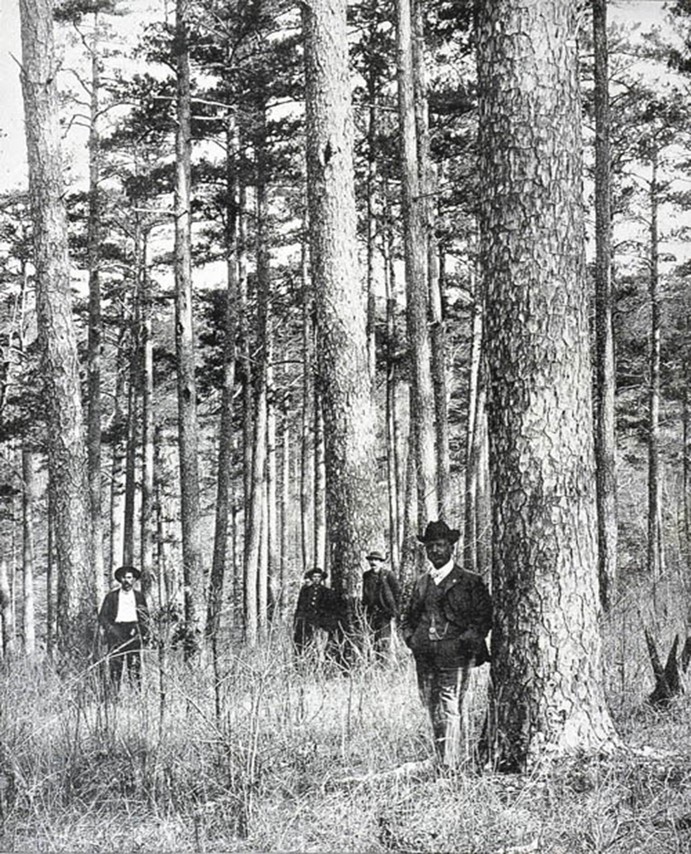

Since Missouri’s policies and practices of wildfire suppression were implemented in the early 1900s, our plant communities and habitat have changed drastically. Forest canopies and midstories have closed, preventing light from reaching the forest floor. Woody vegetation has taken over what were once huge prairies. The photograph to the left is a great example of what shortleaf pine forests would have looked like prior to fire suppression. It was taken in the early 1900’s in the historic pineries of SE Missouri. Shortleaf pine was the dominant species in the region, allowing an incredibly diverse understory to flourish. Now, however, these forests are composed of different species that grow in ways that prevent sunlight from reaching the forest floor, suppressing native grasses and forbs. Fire has the potential to not only to reverse these changes, but strengthen remaining forests (Robinson & Doolen, 2023).

Keep reading to find out more about Missouri’s current fire needs or, learn about the benefits of fire on Missouri’s ecosystems!